The default model for how teaching is supposed to work is that an adult decides what a child needs to learn and by when, then sets about trying to make that happen, using every tool at her disposal: lectures, tests, homework, punishments, rewards. Teaching this way is often very hard, frustrating work for both the child and the teacher, and then, at a certain point, the child gets it.

I've had the good fortune to have always worked in a place where teaching is defined differently. It starts by disposing with the idea that the adult gets to decide what a child is going to learn. The teacher's role is to create a relationship with each child, to listen to him, to play with him, and to often step back and observe him in his play. The art of teaching in this model comes in figuring out what the child is ready to learn, where he is trying to go, then to step in with the right words, or tools, or ideas, or questions. And in that moment, the child gets it, circumventing all the frustrating work that is necessary when a child is not ready. No two children are ready to learn the same things at the same time. It's why you can't package up education and sell it like a product.

There are a couple children in

this year's Pre-K class who have always been fascinated with storytelling, often asking me to

"play a story," but as this year as progressed, the entire group has become almost obsessed with the process of creating stories. We convene each Tuesday afternoon to have lunch together and for the past couple months, they've urged me to "tell a story." What they mean, however, is that they want me to

start telling a story and they want it to be about them. Yesterday's story started like this:

"Once upon a time the Pre-K superhero team was eating lunch . . ."

I was interrupted, and not for the last time, "I'm not a superhero, I'm a princess."

"I'm a queen."

"Okay . . . Once upon a time the Pre-K superhero and princess and queen team were eating lunch, when they heard a tiny voice saying, 'Help, help, help.' Superhero Isaac, who has super power hearing, said, 'The cries are coming from that bridge over there!'" And I pointed out the window toward the Aurora Bridge. "So everyone climbed on the table and Liam, who is super strong, picked up the table . . ."

"I'm super strong, too."

"Me too!"

And each of the five boys told us that he was super strong as did Audrey, leaving only Maya not claiming that super power.

"Okay . . . So Maya climbed on the table, and the rest of the Pre-K team picked up the table and carried it all the way to the bridge, but when they got there they saw nothing. They could hear the tiny voice saying, 'Help, help, help,' but there was no one there."

Liam said, "They're invisible!"

So I continued, "Liam thought they might be invisible, so everyone put on their invisible-seeing goggles and still couldn't see anyone. But the tiny voice kept calling, 'Help, help, help."

At this point the kids took things over, each proposing more and more outlandish ideas for why we couldn't see the person who needed our help. Finally we decided that he must be very small and was trapped under a leaf. We then created more complications, but finally the Pre-K superhero and princess and queen team rescued our tiny person.

We then immediately launched into another story.

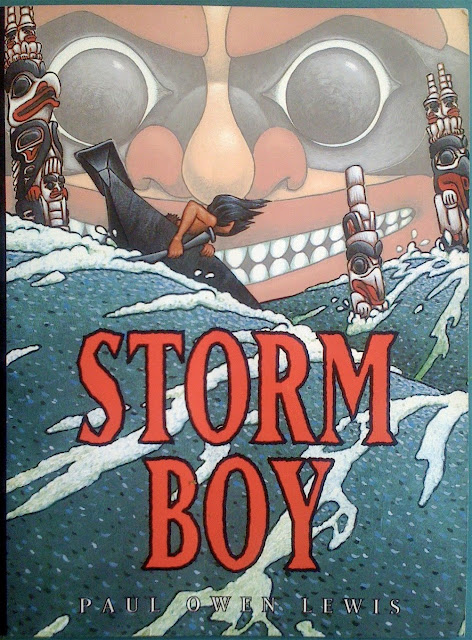

I first read Sendak's great classic, the story of Max, who is sent to his room, then goes on an adventure to a strange land, where he befriends large, frightening creatures, has a "wild rumpus," grows to miss home, then returns there. In the spirit of our former group story telling, it was not a straight read-through, as there was quite a bit to discuss and notice about this short, dense story. I then read Storm Boy (Paul Owen Lewis), announcing, "This is the same story." For those who don't know this book, it's a more modern classic, the story of a chief's son who is fishing alone, when he suddenly finds himself on an adventure in a strange land, where he befriends large, frightening creatures, has a rumpus reminiscent of Max's, grows to miss home, then returns there. This experience was almost more of a conversation than a read-through, as we discussed and debated the finer points of this short, dense story, identifying reasons why Storm Boy's was "the same story" as Max's.

It was miraculous how the children, working together, often wrestling and writhing, but never losing their focus, "got" this seemingly impromptu lesson in comparative lit. We took these two short (both are less than 500 words) stories apart, investigating and comparing each piece, discussing plot and theme and character. We particularly dug into Storm Boy, a book that I've learned contains mysteries that inquiring minds want to solve: What is meant by "under a strange sky?" Who are these large creatures who have what look like "killer whale" costumes hanging on their walls? Why do they eat fish that are not cut up or cooked?

And then the moment came when Mason literally said, "I get it!" He proposed his theory that Storm Boy had fallen into the water and "drowned down to the bottom" where he met the "big people" and had his adventure. It was a key that opened the rest of the story for everyone. We figured out that these weren't people, but rather orca whales. This is when I introduced a bit of Tlingit mythology, the idea that all animals are people too, they just put on costumes to go out into the world. And Liam said, "That's why they had those killer whale costumes!"

The children were ready for this discussion and it flowed like a beautiful song, epiphanies piling one atop another. This was deep learning and it was easy.

By the time we were finished discussing literature like this, we'd used up the time I'd planned to use for something else, so instead, I continued our session by reading Sam, Who Was Swallowed By a Shark (Phyllis Root). Frankly, this isn't nearly as well written or conceived as the other two books, but that could be said of almost any book when compared to those classics. This is the story of a river rat who dreams of going off to sea. The children immediately saw the connection to the other books, a protagonist who would go on an adventure, and settled in for the story. There was much less discussion of this story as I read, probably because the adventure never really comes. The whole story is about how Sam prepares for his adventure, building his "sea going sailboat" as his neighbors stop by to kibitz and cast mild aspersions on his plans. But Sam clings to his "heart's desire" and finally, in the final pages of the book, sets out. The "adventure" is told through the eyes of those who are left behind, speculating that he was lost in a storm or "swallowed by a shark," before they receive a note from Sam assuring them that "I am happy." The final page is a picture of Sam's boat on the water, sailing toward the horizon.

When I read, "The end," Liam said, "No!" The rest of the children sat silently, staring at the pages that had left them high and dry. I showed them that there was no more to the story, but they weren't going to have it, taking turns speculating on what happened next, working together to construct a story that was "the same" as the other two, demonstrating that they had understood the lesson for which they had been ready and had constructed together.

I put a lot of time and effort into this blog. If you'd like to support me please consider a small contribution to the cause. Thank you!

4 comments:

Another great post as usual, Tom! Love all your inspirational work!

Storm Boy is over the top brilliant - thanks for turning us on to Paul Owen Lewis. Frog Girl is pretty awesome too.

Yes! When the child is ready.

I need to read Storm Boy!

Thanks, John

Very beautiful told teacher Tom!

Just the other day I watched Where the Wild things are on TV, and wanted to read it. Have to go to the libery. I love good childrens books and read them for my own pleasure as my grandchildren have moved on to "bigger" books now. Thank you for the story. Hanne in Denmark.

Post a Comment