When our daughter Josephine was born, we lived a few blocks from the Seattle Art Museum and I got it into my head that I wanted our child to grow up feeling a sense of ownership over their/our collection. That said, even as a brand spanking new parent, I knew that one of the frustrations of taking young children to a traditional art museum would be that they were not going to naturally dig on the conventional adult method of working our way through the artwork one by one, gallery by gallery, which is what we do, at least in part, because we are aware we paid admission and at some level we're striving to get our money's worth. To take away that pressure, I bought our family a membership so that we could have no qualms about just stopping by for 5-10 minute visits, often to look at a single painting.

All the photos in this post are iPhone snapshots of color prints from

the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Metropolitan Seminar in Arts book

series, published in the 1950's. Please, please find better photos of these

paintings other places online if you really want to look at them. This one

is "Actor Dancing" by Kiyotada.

Often, as we passed the museum's front doors, Josephine would say something like, "I want to see Jesus whacking those guys," and we would divert ourselves from the sidewalk to a painting (I'm sorry I don't know by whom) of Christ driving the money lenders from the temple. We would often just sit on one of the benches "watching" a painting like one does a television, talking about what we saw. I specifically recall Josephine taking a shine to a work by Cindy Sherman, a contemporary artist who photographs herself in often bizarre and disturbing, but always arresting tableaus. In particular, I recall a piece in which she was apparently a queen breast-feeding a baby. We had a story we told one another about this, repeating it and adding to it each time we visited. It was meaningful to us that the queen was not looking at her baby, but instead looking pointedly "off camera," at something else that held her attention.

When I became a teacher, I wanted to try to recreate this type of experience with the children I taught, but it's not as simple with a group as it was with a single child whose interests and mode of learning I could follow without having to consider all those other interests and modes of learning. If she was in the mood for racing through the maze of galleries instead of figuring out the "stories" of the paintings, using the artwork instead as landmarks in a game of getting lost and found, so be it, but once you start adding other children to the mix, it becomes a different kind of experience.

My wife and I own a terrific set of books entitled

Metropolitan Seminars In Art, published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art during the 1950's, designed as a study-at-home educational guide. Included in each of the books are dozens of removable color prints of masterpieces. Many years ago, I had the idea of taking a selection of these prints into school as "conversation pieces" for our

Pre-K class. Some years they have lead to remarkable explorations of art, other times they've wound up on the floor being trod upon by energetic preschoolers with better things to do.

My idea for this year was that I would spread the prints out on the carpet and we would take some time to freely examine and talk about them. I've found that, as I did with Josephine, talking to the children about the "stories" we may or may not see in the paintings is a good way to start a dialog. Sometimes, of course, there is something in the subject matter that the kids want to start with (the depiction of guns or crowns often does this), but almost always, if the painting is going to hold their interest, there must be a way to support some sort of narrative. And I will freely admit that this may simply be a function of me being the teacher, a guy for whom literature sits on the throne in the hierarchy of art-forms.

Sylvia identified the hunting scenes in the background of this busy painting entitled

"The Journey of the Magi" by Benozzo Gozzoli

I was prepared for the activity to then go in pretty much any direction, including just packing it all away and doing something else, but I

hoped that we would settle on 3-4 of our favorites, then break into groups to elaborate on our painting-stories, which would be transcribed by an adult, then proudly read aloud. I had clipboards charged with paper at hand to aid us in this eventuality.

We thought Picasso's "The Studio" looked like robots.

As the group fully assembled (some of us were still finishing eating our lunch as the activity began) we resorted to the conventional circle time system of me sitting in front with the prints. I suggested that we decide together which ones "tell a story" and which ones do not. We created two categories in which to separate them: "Maybe" and "No." There might have been better ways to divide them up, but that's what came to us. As it turns out, only one of the 17 prints I brought with me wound up in the "No" pile. And instead of quickly going through them, we wound up actually telling the stories we discovered as we went.

Braque's "Musical Form" was the lone print that landed in our "No" pile.

When they asked me what the words said, I tried reading them with

a French pronunciation. We had a brief argument about how I was

pronouncing the letter "J."

All told, between the free-form and formalized discussions, this group of eight 5-year-olds spent 40 minutes discussing great paintings.

Forty minutes! I was prepared to ditch it at any time, but we kept right on going until I felt I detected the beginnings of restlessness. But come on! That's almost as long as a college-level classroom session on art history, and in our version, no one was dozing off. We never made it to the clipboards.

Now I understand that this next part may be where

you doze off, but I was so inspired by our discussion that I've spent this morning further educating myself on what it was we were really looking at. Don't let anyone tell you that great art isn't for young children: traditional museums might not be, and traditional art discussions may not be, but we nevertheless talked about art, some of it from the middle ages, for 40 minutes!

Saint Anthony Tempted by the Devil in the Form of a WomanPainted by Christofano di Francesco (usually known as Sassetta) around 1450, this simple painting portrays Saint Anthony, a religious hermit who lives in a desert, being sexually tempted. Art academic types see a sinister face on the woman. She is, apparently, attempting to bewitch St. Anthony by standing so as to reveal her female form. As I understand this type of painting, we can see the evil wings protruding from her back, but St. Anthony cannot, just as St. Anthony's halo would be invisible to the woman.

The real story of this painting, according to Jody, is that "the guy" lives in that red house. The female figure is a dragon (the Satanic wings do indeed look dragon-like) and "the guy" is going back into his house to get away from the dragon. The thing around the guy's head (the halo) is a "weird hat." I think this is either a testament to Jody's interpretive skills, the artist's ability, or both, in that Jody was able to come so close to the painting's "meaning" without the benefit of any of the back story. Jody also described the setting (desert) as "ancient," which he later explained means "beautiful."

Liberty Leading the People

By Eugene Delacroix, the leader of the Romantic school of French painting in 1830, the bare-breasted (and nipple-less) Liberty leads the people in their toppling of Charles X. She seems to be standing on a pile of corpses. The living people are of all social classes. I figured the kids would find this to be an exciting painting that would lend itself to a nice discussion about war or violence in general.

The children agreed in our discussion that this would make a good story, but really remarked on nothing but the dead bodies and the guns. I found it interesting that none of them said a word about Liberty herself. While looking at this, Sadie told me about a movie she has at her house in which someone dies, "but only at the end." She thought that this painting must be the end of the story, and for at least some of the figures portrayed here, it was. This may explain why we had so little to say.

Several children drew connections between this painting and Gericault's "The Raft of the Medusa," mainly with regard to the pile of dead bodies.

We had a discussion about Medusa (Sylvia knew that she could turn people into stone). Some of us had earlier connected this painting to Bruegel the Elder's "The Fall of Icarus," not because of the Greek mythology connection, but because we decided that the people on the raft must be pirates and that the ship in Breugel's painting was a better depiction of their pirate ship.

We did a lot of this mixing and matching of paintings, especially during the free-form examination of the prints.

Into the World There Came a Soul Named Ida

This intense painting by Ivan Albright depicts an aging woman sitting at her vanity, looking at her reflection in a hand mirror. Critics, and the artist himself, see this painting as a metaphor for life lending itself to death: that life is the mere precursor to death. (As an aside, this is a painting I'd love to have on my own walls, but let me tell you, I'd never agree to model for this artist!)

The children seemed to agree with Jody's interpretation, that this painting tells the story of a woman turning into a monster. What magnificent and spot-on understanding, I think, of the internal dialog of Ida, who appears to be merely going through the motions of maintaining a fiction of youth. At first the kids identified the hand mirror as a hand mirror, but as we talked most of them seemed to think that it was, in fact, some sort of stringed instrument, "like a guitar." Sienna suggested that perhaps she was going to play it to make herself happier.

Rhythm of Straight Lines

Mondrian is a favorite of early childhood educators because his oeuvre lends itself so well to imitation in the classroom.

When I first showed this to the kids, they didn't have much to say. I said, "It reminds me of roads." Violet declared, "It's a maze!" I used my finger to follow the black lines. "You have to go to all the colors!" So I did. Violet then suggested that the artist wanted us to fill in all the white parts. We agreed it would be a good art project to make one of these, all white, for the kids to color in. No one, however, seemed to think it would make much of a story.

Saint Catherine

Painted in the 1400's by a Dutch artist referred to as Master of the Saint Lucy Legend, this painting depicts the probably fictional virgin saint reading a book because according to her legend she was a young woman of superior intelligence and great beauty. I believe the dark male figure at her feet is the Roman Emperor Maxentius who she defeated by converting everyone around him to Christianity, including his wife, and who ultimately beheaded her, making her a martyr.

This was easily the most remarked upon painting by the kids. There was disagreement about whether she was a queen or a princess (she was, in fact, a princess). Some of them felt the dark figure was there to protect her, others thought he was her enemy. In the background is her castle, we decided, or perhaps her "city." I tried to get them to speculate about the book in her hand, but there was at first a lot of shrugged shoulders. Then Sasha clarified matters decisively, "That's the Virgin Mary. My Nana told me all about her." I asked, "Oh, I wonder what kind of book the Virgin Mary would be reading?" She thought, then replied, "Probably a book of prayers." This, I thought, was a special insight, one that was really not too far off the mark. Often solitary female figures in paintings from the middle ages turn out to be the Madonna, and while I'm not knowledgeable about Catholic saints, this one sounds like she's right up there near the top of the hierarchy.

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

This one of Picasso's best known paintings, a scandalous, wild depiction of bold, nude prostitutes. Many people consider this painting to be one of the most important in the development of cubism, and indeed, modern art in general.

Sadie took a strong interest in this one, saying that it was a painting of people lying on towels on the beach. She was pretty sure that only some of them were "girls," while the ones with tribal mask looking faces were "boys." As she made her distinctions she showed her understanding of gender anatomy by pointing at the figure's chests. She thought about the one in the center for a bit, finally deciding that it was a boy, based (if I followed her gaze correctly) upon the secondary clue of her apparently short hair.

The Wyndham Sisters

I don't know anything about John Singer Sargent other than what I think I've learned about him through his paintings, and from that I judge him to be something of a prig, creating these anachronistic conventional portraits of society-types during the era in which the art world was being infused with modernism and democracy. Fans admire his ability to evoke the realistic style of an earlier time, while making it contemporary through his admittedly masterful brush work and "bold" composition.

As one might expect, the girls in particular were drawn to this picture, although none of them identified these beautiful young women in flowing gowns as princesses. Sylvia liked that they were sitting on "cushions." During our group discussion, we talked about the directions of their various gazes, noting that the girl (we were calling them girls) in the center was always looking right at "you," no matter where you were. One of the children mentioned that the dresses reminded her of a bridal gown she had once seen and we then decided as a group that they must all be brides. I read them the title of the piece, "The Wyndham Sisters," and that somehow, seemed to settle things. (For better or worse, having read the title, the children then began to demand I read them the titles of all the subsequent pictures we discussed. On the one hand it colored their interpretations from that point onward; on the other I admire that they were thinking deeply enough about what we were doing to want every clue they could get.)

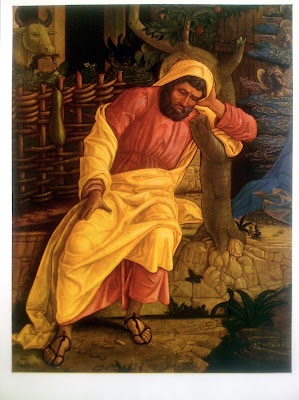

I was not aware until later that this was merely a detail from a small piece by Italian Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna. This is, in fact, a sleeping Joseph, while the rest of the painting depicts Mary, baby Jesus and, you know, the adoring shepards. Interestingly, our discussion of this seems to have been hampered by our lack of that information. The children identified the man as sad and we spent several minutes proposing our ideas for why he might be sad, but without anything else to go on, the discussion, quite rightly, fell flat. You can't pick great artwork apart to understand it -- you have to have the whole thing!

Ia Orana Maria

This Madonna and Child themed painting by Paul Gauguin served as sort of a starting point for a series of paintings depicting Polynesian religion. I picked this one to show to the kids mostly because of the bold colors. The children didn't pick up on the religious aspects, although that might have changed had we noticed the angel there behind the two figures at the center of the canvas. The focus was mostly on the mother figure, which we identified as a mother and a child, which we identified as

her child. At some point one of the kids used the word "tropical" and that lead several of us to reflect on trips to Hawaii or Mexico.

As you no doubt noticed, our conversation didn't stick strictly to art, but as great art should, it sparked us to contemplate our wider world. I actually have more to say about how we extended this exploration later in the day and week, but this post is already too long and I'm ready to get about my Saturday, so I'll save it for tomorrow.

I will, however, thank the Pre-K children for helping me to come to a sense of "ownership" over these great works of art.

I put a lot of time and effort into this blog. If you'd like to support me please consider a small contribution to the cause. Thank you!